Architecture and landscape are often treated as separate worlds one focused on buildings, the other on terrain and ecology. But the way we design our cities is changing. A growing number of architects and landscape architects now see the two as inseparable, working together to create places that are resilient, human-centred, and deeply connected to their surroundings.

For a long time, landscape was treated as scenery, something that complemented architecture but didn’t shape it. It can guide movement, create atmosphere, and define how people relate to a place.

Thinking this way positions landscape as infrastructure, ecology, and experience all at once. Stormwater systems, green infrastructure, sloped topographies, and biodiversity corridors aren’t add-ons they’re core components of design. When architects work with natural systems instead of against them, buildings become part of a larger ecological network.

This approach supports resilient cities, reduces environmental impact, and creates environments that feel intuitive and rooted in place. It also aligns with how people want to live todaycloser to nature, with spaces that adapt to climate, culture, and daily use.

Snøhetta is one of the clearest examples of what happens when architecture and landscape design evolve together from the start. Their teams work side by side architects, landscape architects, interior designers, and environmental specialists all contributing to a shared process.

This collaboration shapes spaces that feel effortless and connected. Their landscape work prioritises:

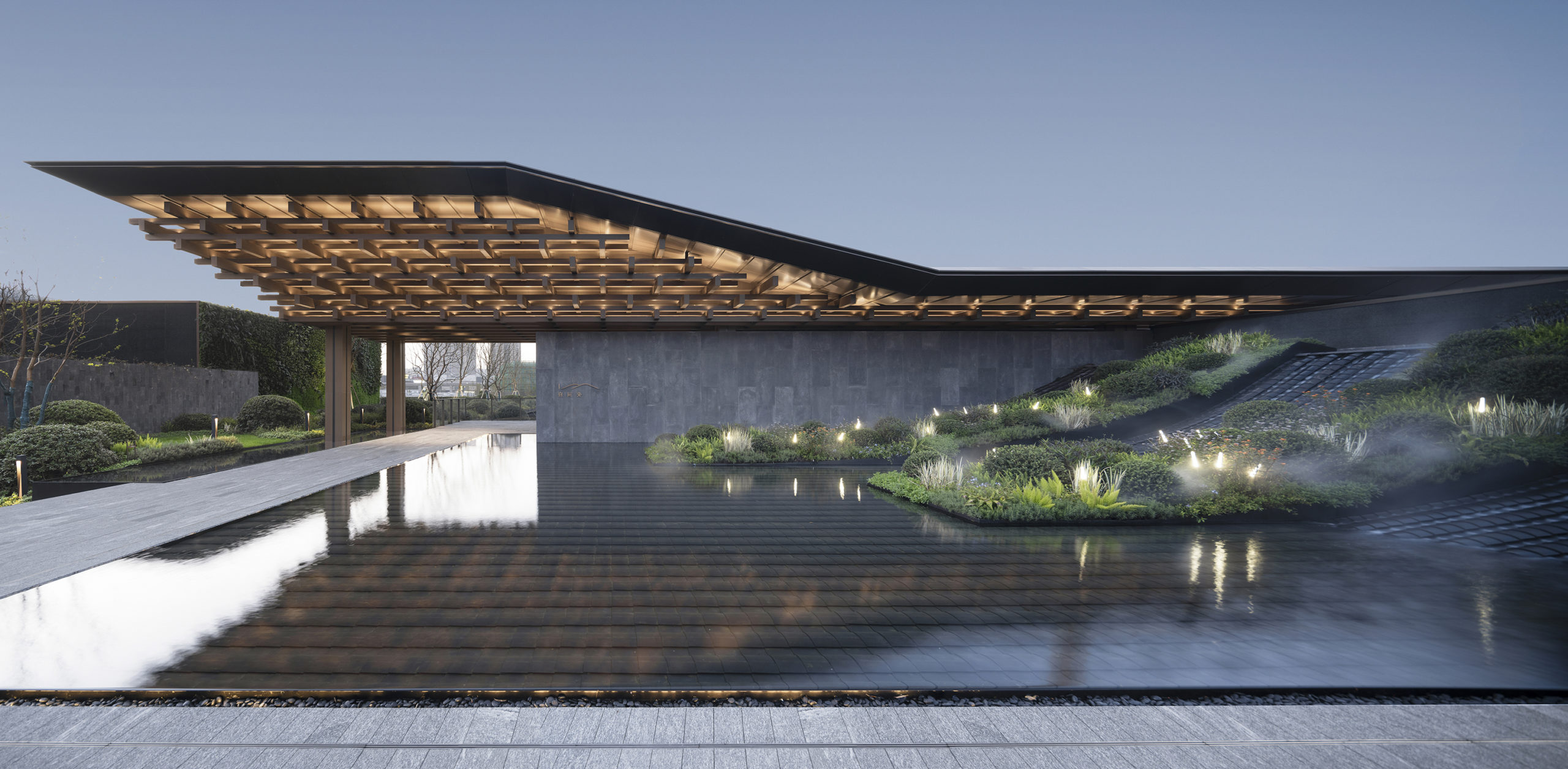

Their projects often blur boundaries: a plaza becomes part of a building; a roof becomes a hill; pathways follow the logic of natural landforms. The result is an immersive environment where architecture and landscape coexist, each strengthening the other.

As World Landscape Architect highlights, landscape architecture today is a dynamic field that blends ecology, engineering, culture, and public life. It’s far more than parks and plantings, it’s about designing systems and spaces that support both people and the environment.

Landscapes now actively contribute to city health.

Examples include:

These spaces are as functional as they are enjoyable.

Landscape design often reflects the character and history of a place. Understanding vernacular landscapes, indigenous knowledge, and long-standing natural patterns leads to designs that feel meaningful and authentic.

Modern landscapes are created to be lived in, walked, touched, explored. They shape sensory experiences and encourage people to connect with natural systems, even in dense urban settings.

This framework pushes architecture to think beyond the building footprint. By embracing site-specific design, adaptive reuse, urban ecology, and holistic planning, architects and landscape architects can create environments that feel complete and connected.

When architecture functions as landscape, buildings respond to the terrain and environment rather than dominating them. A few design strategies illustrate this clearly:

Buildings may follow the slope of a hill, integrate green roofs as extensions of the terrain, or create circulation paths that mimic natural flows. Material tectonics and sustainable materials help reinforce this connection.

Projects can double as pollinator routes, shade structures, or water filtration systems. Instead of separating building and landscape, both work together to support urban ecology.

Transitions between inside and out can be gentle rather than abrupt. This might look like:

Good design considers everyone who uses the space, visitors, residents, wildlife, and living systems. The result is an environment that feels balanced and alive.

Designing for ecological resilience means creating forms that adapt to flood cycles, temperature shifts, and long-term environmental change.

These strategies pull architectural ecology and environmental integration directly into the core of design thinking.

Bringing architecture and landscape together isn’t just an aesthetic choice, it’s a long-term strategy for healthier cities and communities.

Nature-based solutions offer reliable ways to manage heat, water, and air quality often more sustainably than engineered systems.

Biophilic design, greenery, and sensory-rich environments support mental health, comfort, and social connection.

When buildings respond to place, they honour local identity and environmental conditions. This helps create spaces that feel grounded and genuine.

Combining soft and hard infrastructure leads to cities that use fewer resources and can adjust to changing environmental conditions.

When architecture, urbanism, and landscape architecture work together, the result is a unified environment rather than a collection of disconnected parts.

This integrated mindset is becoming central to sustainable urbanism and will shape how we design cities for decades to come.

The relationship between architecture and landscape is changing, and with it, the way we design the world around us. When buildings are shaped by natural systems, cultural landscapes, and site-specific conditions, they become more resilient, more human, and more meaningful.

For architecture practices, this approach offers new opportunities to create projects that don’t just occupy land, they contribute to it. If you're exploring how to bring architectural and landscape thinking together in your next project, early collaboration with landscape architects and ecological experts can make a measurable difference.

Designing the future means designing with the landscape, not against it.